서양화를 전공했지만 ‘붓’ 놀림의 영상과는 별도의 Printing이 제공하는 또 다른 회화성이 좋아 한동안 판화 작업을 했다. 당연히 피인쇄체인 각종 종이에 대한 공부가 되었고 특히, 우리와 역사적, 정서적으로 밀접한 한지도 접할 수 있었다.

여러 판종 중에 특히 목판화가 주는 칼 맛과 동양적 여백미는 내게 매력적이었고, 그 프린팅을 받아내는 한지는 우리 민족과 역사적, 정서적으로도 밀접하며 그 보존성과 호흡이 가능한 생물성(生物性)으로 작업의 완성도를 높이는 역할이 컸다.

카운팅을 초월하는 천체 중 해와 달은 육안으로 볼 수 있다. 이를 종이에 대입하자면 나는 해는 서양의 종이, 달은 한지라고 여긴다. 이유는 화면을 경계선으로 구분 짓지 않는 한지의 퍼짐이 주는 농담 효과와 호흡할 수 있는 기능에 있다고 본다.

여기서 한지를 달에 비유하는 고찰은 비디오 아트의 아버지로 불리는 백남준도 그의 작업이 “비디오의 모니터를 통해 제시되는 영상은 빛을 발생하는 해가 아닌 간접으로 투영되는 달”이라고 술회한 것과 닿아 있다. 나의 생각은 아마 그가 한지로 만들어진 봉창을 통해 비친 달빛을 경험했다고 여긴다.

나의 작업은 연속되는 제시가 궁극이기에 한때는 심호흡을 주제로 연작하였다. 생명과 모럴을 지키는 들숨ㆍ날숨의 자율성은 마치 빛과 공간을 자연스레 교통시키는 한지와 비견되었다.

첨언으로 인류 최고(最古)의 판목으로 기네스북에 등재된 신라시대의 “무구정광대다라니경”과 우리의 고가치 자산인 팔만대장경도 결국은 한지의 존재와 유관하다고 본다.

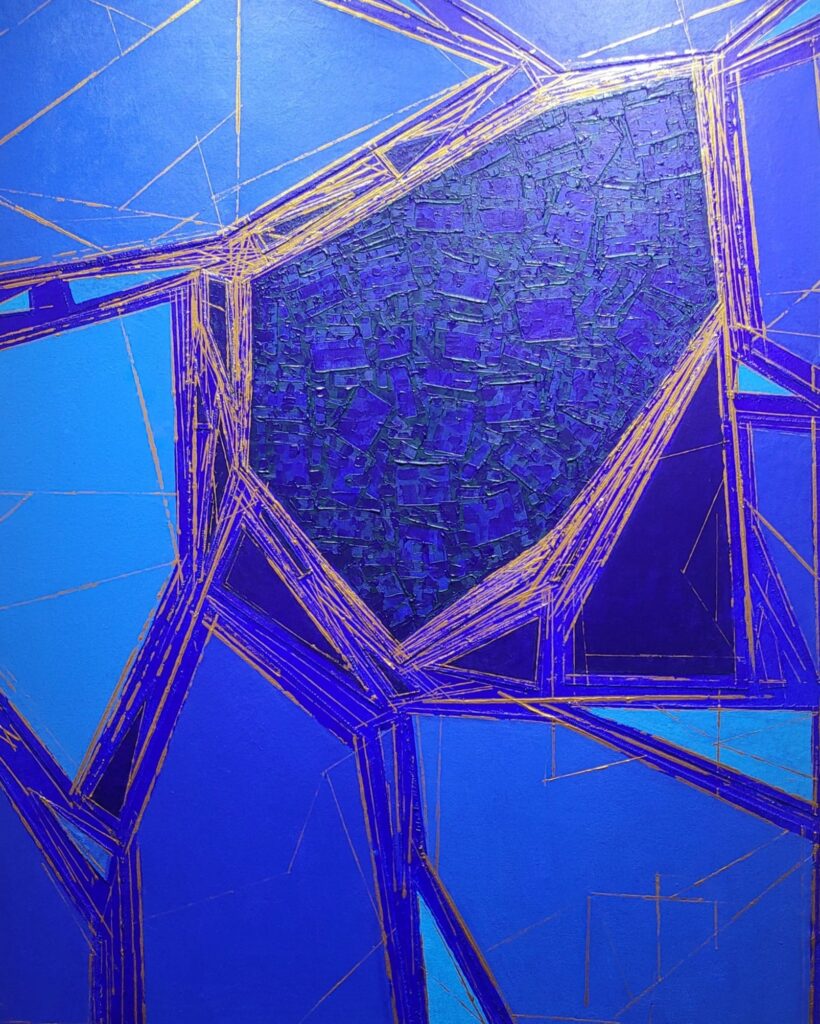

나가는 글로 향후 나의 작업은 페인팅과 프린팅, 그리고 구상과 추상을 들숨 날숨처럼 교통할 것으로 예상되며 우리의 한지를 더욱 활용할 것이라 여겨본다.

화가 안영찬

While my background is in Western painting, I found myself drawn to the distinct pictorial quality offered by printing—a quality separate from the imagery created by brushstrokes. This led me to focus on printmaking for quite some time. Naturally, this process involved a deep study of various papers used as printing surfaces, and I eventually encountered Hanji (traditional Korean paper), a material that holds profound historical and emotional significance for us.

Among the various printmaking techniques, I was particularly captivated by the incisive texture—the “taste of the knife”—inherent in woodcuts, as well as the aesthetic of empty space found in Eastern art. Hanji played a crucial role in receiving these prints and elevating the completeness of the work. Its organic vitality, which allows the paper to “breathe,” along with its exceptional durability, resonated deeply with our people’s history and sentiment.

Of the celestial bodies that transcend counting, the Sun and the Moon are visible to the naked eye. If I were to equate these to paper, I consider the Sun to be Western paper and the Moon to be Hanji. The reason lies in Hanji’s ability to breathe and the effect of Nongdam (the gradation of ink)—where the ink spreads naturally without being confined by sharp boundary lines.

This contemplation comparing Hanji to the Moon aligns with the thoughts of Nam June Paik, the Father of Video Art. He once described the images presented through video monitors in his work not as the Sun, which generates its own light, but as the Moon, which shines by indirect projection. I believe his perspective likely stemmed from an experience of seeing moonlight softly filtering through a Bongchang (a traditional window made of Hanji).

Since the ultimate goal of my work is a continuous series of propositions, I once worked on a series under the theme of “Deep Breath.” The autonomy of inhaling and exhaling, which sustains life and morality, was comparable to Hanji, which naturally mediates the interplay between light and space.

As an addendum, I believe that the Mugujeonggwang Daedaranigyeong (the Great Dharani Sutra), recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s oldest woodblock print from the Silla Dynasty, and the Tripitaka Koreana, a high-value cultural asset of Korea, owe their longevity to the existence of Hanji.

In closing, I anticipate that my future work will see painting and printing, as well as the figurative and the abstract, flowing together like an inhalation and exhalation. In this process, I envision utilizing our traditional Hanji even more extensively.

Artist Ahn Young-chan